![]()

Twisting the "String" and Punishing the "Pearls":

The Editing Errors by the Historian Author Redhouse

concerning the Historian Narrator ‘Alī b. al-Ḥasan

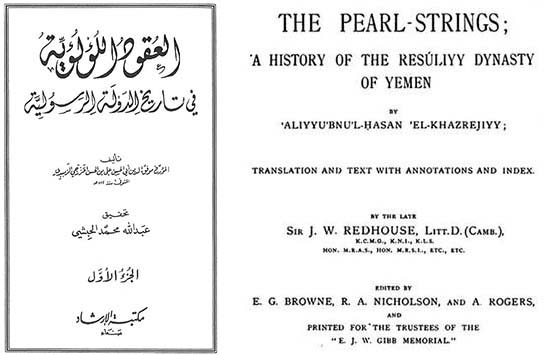

The Redhouse Edition

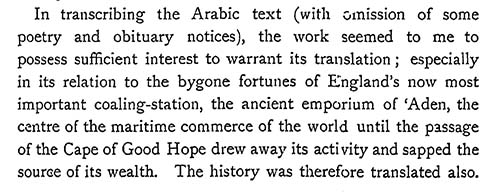

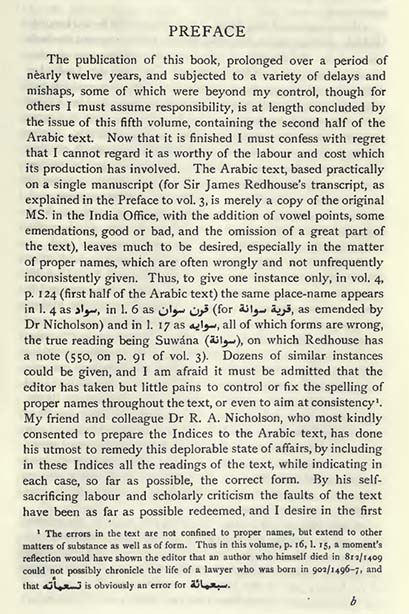

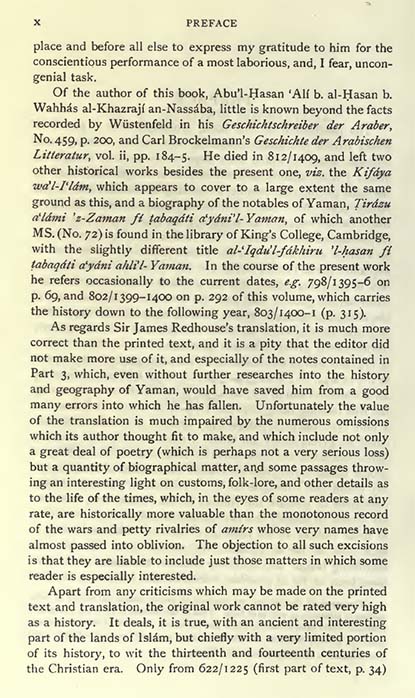

Redhouse said that he undertook his work on the text after having received an honorary doctorate from the University of Cambridge. His interest in doing this is mentioned in his preface, originally written in 1888, to the first edition:

The complete Redhouse edition, published by Brill in Leiden, consisted of five volumes, all of which are readily available online:

Vol. 1 (1906): English translation by Redhouse up to death of al-Malik al-Mu‘ayyad (721/1321)

Vol. 2 (1907): English translation up to the death of al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismā‘īl (803/1400)

Vol. 3 (1908): Annotations to the English translation

Vol. 4 (1913): Arabic translation by Muḥammad ‘Asal up to death of al-Malik al-Mu‘ayyad (721/1321)

Vol. 5 (1918): Arabic translation up to the death of al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismā‘īl (803/1400)

The Arabic volumes 4 and 5 are also available to read online.

His Introduction (vol. 1, pp. 5-41) provides a history of Yemen up until the year 1858, drawing largely on al-Khazrajī for the Islamic history up to the death of al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismā‘īl in 803/1400. The detailed Table of Contents in the English version (vol. 1, pp. xiii-xx) is a quick guide to the subjects covered. The English translation is spread over two volumes, the first ending with the death of al-Malik al-Mu’ayyad in 721/1321 and the second through the death of al-Malik al-Ashraf Ismā‘īl in 803/1400. A third volume contains the many notes, some of which remain useful. For those interesed in Redhouses' approach to transliteration, he provides a detailed discussion of this in an earlier work.

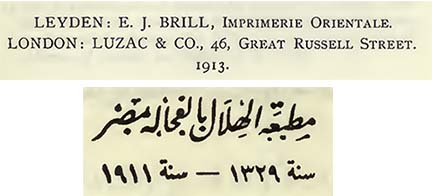

The two Arabic volumes, edited by Shaykh Muḥammad ‘Asal, added a number of poetic excerpts and death notices that Redhouse had not translated. There is some confusion on the date of publication for both the Arabic volumes. For volume 4 The English title says 1913, but the Arabic title page has 1911. The same issue occurs for volume 5, which is 1918 for the English and 1914 for the Arabic. The reason for this is that the original typesetting of the Arabic had to be redone for the Brill edition, given the massive number of errors in the original Arabic version in Cairo, but the title page on the earlier edition was simply copied.

There is also a notice of printing errors, provided here. In the 5th volume there is a preface by E. G. Browne, lamenting the errors in the Arabic text, as noted below:

With apologies to Edmund Browne, there are those of us who are "especially interested" in the matters recorded by al-Khazrajī. A reviewer in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, writing in 1919, said that the "text of the Arabic volumes swarms with misprints, only a small fraction of which is corrected in the tables of errata prefixed to the fifth volume."

Volume 5 has a list of the Arabic parts omitted by Redhouse in his translation (pp. xvii,xviii). For both Arabic volumes there is an index of personal names (pp. 421-438) and places, tribes, important animals and days (pp. 439-480) and titles of books and poems (pp. 481-486), but there is no list of errors for the 5th volume.

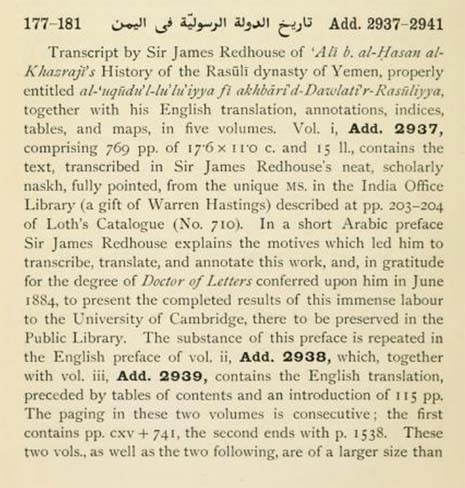

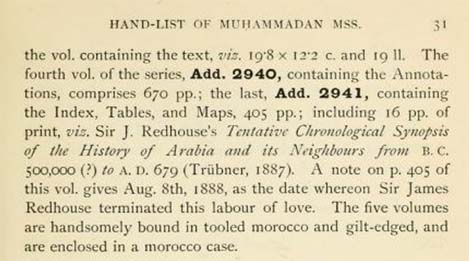

The handwritten manuscript of Redhouse is housed in the library of the University of Cambridge, as described by E. G. Browne in his A Hand-List of the Muḥammadan Manuscripts… (Cambridge, 1900, pp. 30-31). This was copied from the original (Loth 710) in the India Office Library.

1911/1914 Arabic Edition by Muḥammad ‘Asal

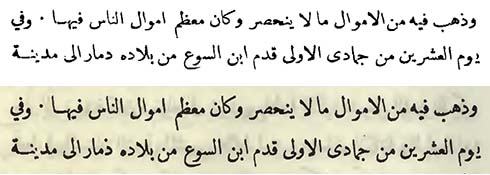

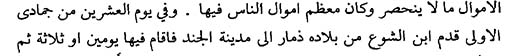

An earlier version of the Arabic by the same editor was published in Cairo in 1911-1914 at the Maṭba‘a al-Hilāl al-Fajjāla. This prior edition should be totally avoided as it has errors on almost every page. At the start of the second volume there is a list of hundreds of printing errors stretching for 14 pages for Volume 1 and 6 pages for volume 2. This version, which can be found on the Internet had to be reset for the Brill edition. An example of a glaring error is provided below, where the original 1914 Arabic printing (top) mispelled the town of Dhamār as Damār, which was corrected in the Brill edition of 1918 (bottom), both on p. 29.

There is a version online at the Arabic wikisource that claims to be the 1914 edition of the second volume, but in fact it is different from both the original Egyptian 1914 and the Brill 1918. For example the town of Dhamār is correct, but there is clearly a different typesetting (p. 34).

It was republished in 1403/1983 the Markaz al-Dirāsāt wa-al-Buḥūth al-Yamanī in Ṣan‘ā’ and printed at Dār al-Adāb in Beirut. The second edition has a preface by Muḥammad ‘Alī al-Akwa‘, but there are no indices. Qadi al-Akwa‘ describes his work on the Arabic text as follows:

This edition is available online in a searchable format. There is also a version of the Akwa‘ edition (volume 2) online at the Arabic Wikisource without attribution to al-Akwa‘.

1994/2009 Arabic Edition by ‘Abd Allāh al-Ḥibshī

This was published by Maktabat al-Madbūlī in Cairo in 1994 and by Maktaba al-Irshād in Ṣan‘ā’ in 2009. The editor consulted two main manuscripts; the one in the India Library (perhaps from the published Redhouse edition) as well as an old one in the Western library of the Great Mosque in Ṣan‘ā’, the latter is missing the last part of the text. Although al-Ḥibshī apparently did not consult them, he notes that there is a copy in the Maktabat al-Awqāf al-Markazīya in al-Sulāymānīya, Iraq (Maktabat al-Bābāniyīn, 7/18) and another in a mosque in Riyadh.

Postscript: On the Reading and Citation of Flawed Editions

It is obvious that the important works of the Rasulid historian al-Khazrajī deserve critical editions. The Redhouse edition, which is the main one cited by Western scholars for over a century, had admitted flaws when it was published. Sir James was an accomplished scholar, although his expertise was more in Ottoman Turkish, but he died more than a decade before work began on his handwritten manuscript. As the reviewer in 1918 noted at the time: "... the reader must be left to correct or supplement as required passages which represent views of Oriental history current forty or fufty years ago." How much more so is the situation some 130 or so years after Redhouse completed his work. The editors Browne and Nicolson for the Gibb Trust were qualified for the task a century ago, but neither had first-hand knowledge of Yemen nor the textual tradition in Yemen.

The English translation is useful as a guide, but its late 19th century prose style, quixotic poetic renderings and inconsistent transliteration scheme make it virtually impossible to quote directly. No serious reader can use the English without having the Arabic alongside. Yet, as the reviewer in 1918 pointed out: "Anyone who attempts to read the original [Arabic version] must keep Sir James's translation open before him, or he will meet with difficulties on every page." This is because the Arabic edition prepared by the Egyptian Muḥammad ‘Asal, a teacher of Arabic at Cambridge, is itself full of errors. The Arabic text was set up in Cairo from a photograph of the copy in the India Office. The Arabic tmanuscript, the date of which is not known, contained errors that Redhouse corrected in his translation and further errors that were introduced in the printing process.

It is almost always the case that published editions of historical texts , even when edited by careful scholars, will have some errors. This may be due to not noticing an error in the original manuscript (especially if there is only a single or a few copies), a simple oversight or the inevitable printing error. Editions of major Arabic geographical and historical texts from more than a century ago were almost always made by Western scholars who often only had textual knowledge of the region or subject covered. Yet many of these remain vital for research, such as the volumes in Brill's Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum, even though numerous Arabic editions have appeared since then.

In the case of the ‘Uqūd, as noted above, there are several editions available. The edition published in 1983 is an update of the 1911 by the Yemeni qadi Muḥammad ‘Alī al-Akwa‘, who edited a number of important Yemeni texts, some from manuscripts in his own possession. The most truthworthy is clearly that edited by ‘Abd Allāh al-Ḥibshī, although that is seldom used by Western scholars.

As a historian who depends on al-Khazrajī, I realize the difficulty in citing editions of al-Khazrajī's text. Since the Brill edition is the most commonly used, I will cite it, but in the future this will be always providing both the pages for the relevant English and the Arabic volumes. This can consume a lot of time, since neither is yet digitized and one has to match up the links to the pages of the original manuscript that appears in the margins of the volumes. In cases where it is important to cite the more authoritative, but still not critical edition of al-Ḥibshī, I add that as well.

This page was created and is maintained by the webshaykh Daniel Martin Varisco